![]() |

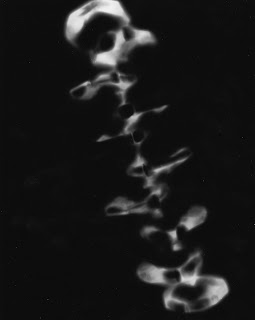

| Man-Kit Lam, 2005 |

For those with a yen for travel, we've gathered a few shows you may want to catch before the year is out. All include chemigrams either solely or in part or, in Ms Rossiter's case, include what might be called a chemigramic inflection - and for that reason alone they're all worth seeing, besides the utter beauty and mystery of them. If we've missed your show, please post a comment and we'll fix it.

Pierre Cordier Paris Photo, HackelBury Gallery, November 10-13, 2011, Grand Palais, Paris, France

Dominic Man-Kit LamInk Art: a world without rules, September 2011 & February 2012, Novel Plaza, 128 West Nanjing Road, Shanghai, China

Alison Rossiter Art Platform LA, Yossi Milo Gallery, October 1-3, 2011, LA Mart, Los Angeles, California, USA

Alison Rossiter Paris Photo, Stephen Bulger Gallery, November 10-13, 2011, Grand Palais, Paris, France

Edward MapplethorpeThe Variations, October 5 - November 12, 2011, Dubner Moderne, rue du Grand-Chêne 6, Lausanne, Switzerland

Norman SarachekEmerging Artists Annual Showcase, November 4, 2011, Allure West Studios, 15 E State St, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, USA

Matthew HigginsPingyao International Photography Festival, September 1 - September 30, 2011, Pingyao, Shanxi Province, China

Nolan PreeceContinuitive: Connections Between Parallel Directions, Dec 2011 - January 2012, Truckee Meadows Community College, 7000 Dandini Blvd, Reno, NV, USA

Douglas CollinsNew Prints 2011 Selected by Trenton Doyle Hancock, October 3, 2011 - March 28, 2012, Pfizer Corporation, 235 E 42 St, New York, New York, USA

just closed:

Dominic Man-Kit LamSino-French Exhibition of Art Exchange, September 20-22, 2011, National Library Exhibition Center, Beijing, China

Nolan PreeceXhibit, May 13 to August 27, 2011, Preston Contemporary Art Center, 1755 Avenida del Mercado, Mesilla, New Mexico, USA

.jpg)